The Breakthrough

Welcome back.

Last night, I read for NAWP’s wonderful annual Hannukah virtual poetry reading, taking a half hour to duck out of a Hannukah party I was technically hosting. (It’s a longish and not terribly interesting story.) I chose to read a translation, because in truth, I write very little poetry of my own these days. I decided to lean into the martial history of Hannukah, although I have conflicted feelings about that history. Or rather, that historiography.

To put it in a gross oversimplification, there is a certain amount of evidence that Zionism since its formation as an ideology has put considerable resources and intellectual effort into claiming an outsized role for militarism in our understanding of Hannukah and its history. This effort muddies the waters of the past—never particularly crystalline— and makes it unclear whether to our ancestors, Hannukah was a celebration of an ancient Judean military victory or a miracle in the longed-for Temple, or just a nice excuse to fry some potatoes and light a few candles in the winter. It all goes to show that the war on Christmas may be heated, but nothing quite equals the internecine conflicts of my people.

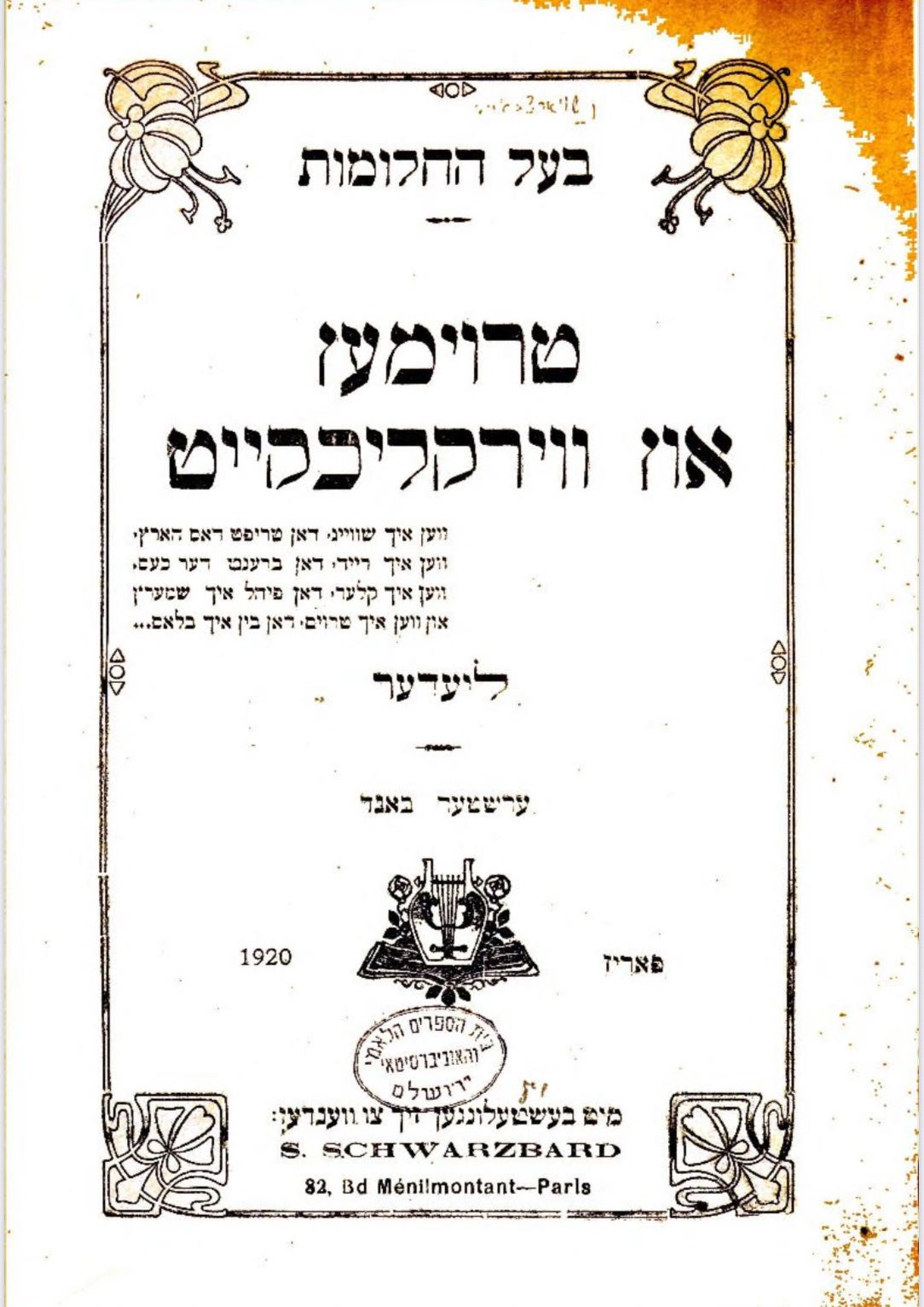

In any case, I decided to read my translation of the prologue to Dreams and Reality, a 1920 collection of poems by Sholem Shvartsbord, published in Paris under his pseudonym Baal Khaloymes, “The Dreamer.”

It’s an odd poem, by an odd poet. Shvartsbord, originally from Bessarabia, like my family, fought with distinction for France’s foreign legion in World War I, and then spent the Russian Revolution in various Anarchist and Bolshevik battalions. Injured and captured by White Russian forces, he managed to use his connections in France to enter exile there. Six years after the publication of the poems in Dreams and Reality, Shvartsbord walked up to the Ukrainian nationalist Simon Petliura, himself in exile in Paris, and shot him 7 times. When arrested, Shvartsbord insisted that he had “killed a greater assassin than himself”, holding Petliura responsible for the pogroms that racked Odesa in the Russian Civil War, pogroms which killed 15 members of Shvartsbord’s family. The jury agreed with him, and he walked. Shvartsbord wrote two autobiographies in Chicago and died in South Africa.

So the poem I read was written by a radical soldier, brewing on disappointment in revolution and revenge. I struggled to find that in the poem. Its language is warlike, yes. But at first glance, I didn’t see the bitterness and sadness I expected. The imagery is almost Wagnerian, and I am tempted to do a revised pass that emphasizes the Germanic elements. But in reading the poem alou, I think I found my way to the soul of Shvartsbord. The key lies in the first and final stanzas. The hero that is Man that is the addressee of the poem, the audience, you, triumphant over a poisonous enemy. Who is that enemy? It is unclear until the final line. Here is the poem in my translation. Let me know what you think.

Prologue to Dreams and Reality, Sholem Shvartsbard, trans. Mordecai Martin

A shield for you, forged of steel and iron strong

A twice sharpened sword in hand, a steadfast grasp

Girded hips, every hand armed

Come out with me to the battlefield, to the world’s stadium:

Show your strength! I call! Follow my bidding!

From thousands of heroes, one stands. This is you, the Hero!

The victory sweetens the victor:

As honey are the spoils, as nectar the plunder.

Further . . . In you, your heart grows so well cold

When your sacrifice approaches with poisoned feet

Your strong arm pierces the breast of your conquered victim

Who falls under you.

You raise your hand. Your sword full bloody

With conqueror’s head whole high. Whole high . . .

Then they will adore, hail, praise your skill,

And every eye will be raised to see you,

And, with deep respect, inspired by your glance and victory,

They will bow their heads before you. They praise, they hold you holy in their hearts.

Exultation on their lips, they gift you words of praise .

The prettiest daughters of your people will braid you laurel wreathes.

Your gaze, your strong manly art, your lovely form will warm them, they’ll grow faint, these magical beautiful goddesses.

Happy will be that breast where your gaze will fall

Wherein deep lies the heart which will resound to your every word.

Happy and joyous and cheerful they will weave unadorned around you.

This could be so beautiful.

It is prepared for you, the King’s table.

The white silver table, full splendid and shining.

The lovely glance also is destined for you

Your word is holy, precious, as the word of God.

Slave and lord, king and serf

Will inscribe it for you yourself, unadorned.

Your wish will always come true,

The kings will grant your desire, the most beautiful of women

Naked and knowable in the bright of day

For the eyes of the whole world.

Only this glows

Just your gaze is all they want in the world.

Man, you stand now at the edge of life

For you, everything is free, everything is in your grasp

There, on a mountain, shrouded in pure silver clouds

Stands a beautiful and wondrous magical palace;

Beside the world, created — it stands there alone.

Pure and immaculate as crystal: Its foundation is built of marble stone.

A bed of wish-gold and strings of pearls is made,

Immaculate, lovely, shining with all sorts of gems.

There stands a marriage canopy, embroidered in the best artisan hand.

The surrounding terraces bloom with everything,

Amber fountains flow always there, without end.

An upswelling of water, silver white, winds quietly through the garden bed,

Between fragrant trees with marvelous huge fruits.

Strolling among the high, dense grasses

A young woman, an enchanted image; a lost princess.

Dreamy, yearningly, she calls out your name.

Birds, trilling, drench her in song.

Accompanying this innocent’s call,

That moment felt in the heart:

Man! Where are you, great hero,---

Conqueror of your God! . . .